How to tell if your child is having a stroke — and where to seek treatment

Most people don’t think kids can have strokes. It’s rare, but when it does happen, the effects can be catastrophic if the child doesn't get the proper treatment.

Parents — and even some medical professionals — sometimes misdiagnose a stroke as a seizure or migraine, which delays life-saving care. And not all hospitals are equipped to treat stroke in children.

To address this problem, two University of Chicago Medicine physicians developed a pediatric stroke protocol to help emergency room staff at Comer Children’s Hospital quickly identify and treat stroke in children of all ages.

The protocol has already saved lives, including that of a 14-year-old boy who was hit in the head by a basketball and suffered a stroke the next day.

“The program’s working extremely well, and it’s something we’re very proud of,” said UChicago Medicine pediatric neurologist Henry David, MD, who developed the protocol with pediatric critical care specialist Casey Stulce, MD. “We’re doing things most other hospitals aren’t doing.”

Here are the doctors’ answers to common questions about pediatric stroke symptoms and treatment:

Who is most at risk for pediatric stroke?

One of every 1,000 babies and 1 in 8,000 children suffer strokes. The odds are slightly higher for children with sickle cell or congenital heart diseases.

What are the two types of pediatric stroke?

The most common is ischemic stroke, which is when a clot forms and blocks blood flow to the brain. Children also can have a hemorrhagic stroke, where blood vessels within the brain rupture and cause internal bleeding.

What are the symptoms of strokes in children?

The highest risk for stroke is right before, during or after a child’s birth. It’s very difficult to notice if a baby is having a stroke, but symptoms may include nonspecific excessive sleepiness and problems breathing and eating.

Symptoms for a stroke in toddlers might include not moving one arm as much as the other, or new vision or balance problems.

In most children, symptoms are similar to a stroke in adults — drooping of the face and/or weakness and numbness of one side of the body, or trouble speaking and walking.

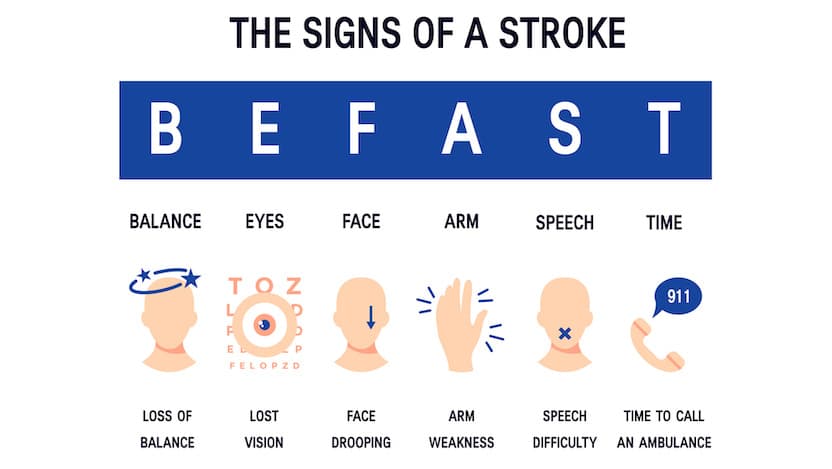

Remember the acronym F.A.S.T. — Face, Arms, Speech, Time. If a child shows symptoms in their face, arms or speech, it’s “time” to call 911, just as you would for an adult.

What type of injuries can cause a stroke in children?

Any serious neck injury, such as whiplash from a car accident, a fall, or a sports collision where the neck bends. “All you need is a tiny microscopic tear in the blood vessel,” David said. “If your child has had a significant neck injury, you want to watch for signs of worsening neck pain, headache and any new signs of weakness.”

How long after an injury does it take for a stroke to happen?

The risk period is within 24 hours after the injury. A clot can mature hours later, and it either dissolves on its own before getting to the brain, or it gets clogged in a vessel and causes a blockage. Once the child starts showing stroke symptoms, such as body numbness, they have about 4 ½ hours to get the best level of treatment, Stulce said.

“Treat this like a pediatric trauma and go to a place where they can treat your child,” Stulce said. “If you spend six, eight or 10 hours at a community hospital that doesn’t have designated pediatric specialists, it’s too late.”

How is pediatric stroke different from adult stroke?

While the symptoms are similar, children have different pathology and blood vessels, and they require specific treatment. Children have strokes for different reasons than adults. In adults, a stroke is often related to decades of chronic hypertension, diabetes or other blood vessel diseases like hyperlipidemia.

But in children, a stroke is more typically related to undiagnosed cardiac defects, fragile connective tissue or blood vessel malformations, or blood clotting disorders such as sickle cell disease. Because of these differences, adult stroke specialists are often unfamiliar with all of the aspects of treating children, David said.

How are pediatric strokes treated?

Doctors restore blood flow to the brain by dissolving the blood clot. This can be done using blood thinners intravenously, via a minimally invasive surgery where a catheter is inserted into a leg vein. At Comer Children’s, state-of-the-art imaging techniques guide the catheter to the clot to remove it or melt it with anticoagulants.

What is Comer Children’s pediatric stroke protocol?

The protocol is a streamlined process for treating children in the ER who are having a stroke.

The effort began with training and simulation sessions for Comer Children’s staff and the creation of a “pediatric stroke code.” If an ER doctor or nurse suspects a young patient is having a stroke, they can activate the code, which pages a team of pediatric stroke specialists and imaging and radiology technicians. This can then accelerate the process of potentially intervening by administering anticoagulants (rapid blood thinners) or bringing patients to the operating room.

“The goal is for no family to have to deal with the devastating effects of their child having a stroke and it not being recognized and treated properly,” Stulce said.

Activation of the stroke code has increased nearly sixfold since Comer Children’s adopted the protocol in 2020. This year, David and Stulce hope to expand their pediatric stroke education efforts to include paramedics and community hospitals.

What does stroke recovery look like for children?

Data has demonstrated that recovery is better for children than adults. The largest period of recovery is in the first 6 to 12 months, depending on the severity of the stroke. It begins at a pediatric rehabilitation facility.

“The survival rate is high, but the disability rate can also be high,” David said. “It depends if someone intervenes and treats the stroke appropriately. Life span can be affected. For example, if the stroke limits your ability to walk, then other chronic medical issues can come into play. The goal is to limit any and all disability so that children can go on and thrive, not just survive.”

Henry David, MD

Henry David, MD, is a pediatric neurologist who specializes in neurocritical care and treats children of all ages with serious neurological conditions who require acute care to long-term treatment. He also is an expert in cerebrovascular disorders, including ischemic stokes and hemorrhagic strokes, and provides comprehensive, compassionate care to patients and their families.

Learn more about Dr. David

Casey Stulce, MD

Casey Stulce, MD, is a specialist in pediatric critical care medicine. She provides care for critically ill infants and children in the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) and pediatric sedation service.

View Dr. Stulce's physician profile