Experimental treatment for macular holes opts for eye drops over surgery

» View an updated story about eye drop treatment for macular holes

"We haven't published anything yet," explained eye surgeon Dimitra Skondra, MD, PhD, about an experimental treatment. "We haven't even designed, much less organized, a clinical trial — although we have an idea how we would like to set it up. For the moment, this is just an idea, an off-label use of common drugs. But we tried this on four patients and it worked for three of them. They recovered without surgery.

"Not all retinal surgeons will like this because it decreases macular hole surgeries, one of the most commonly performed surgeries in a vitreoretinal practice."

A big, dark hole in the retina

Skondra, an assistant professor of ophthalmology and visual science and director of the J. Terry Ernest Ocular Imaging Center at the University of Chicago, is a respected, board-certified retina specialist who focuses on the medical and surgical treatment of vitreoretinal diseases. One of her clinical interests is the treatment of macular holes, a small unraveling of the macula, which is at the center of the retina.

A functioning macula provides the sharp, clear, central vision people need to see fine details, to read or to drive. Even a small gap in this delicate light-sensing tissue can cause blurred and distorted central vision. When someone with a macular hole looks directly at a face, they see a "big dark hole right in the middle," Skondra explained. "It can be very disturbing."

Unfortunately, macular holes are common, especially for people over age 60. Treatment has historically involved vitrectomy, a surgical process to remove the vitreous gel from the middle of the eye. This is a fairly straightforward operation when it comes to the vitreoretinal surgery spectrum "but it is retinal surgery," she said. "Retinal surgery is always a serious surgery. You operate on the retinal surface, a very delicate space. There are always risks."

At the end of the procedure, the surgeon inserts a gas bubble, designed to help close the hole. Patients with the bubble have to maintain a face-down position day and night for several days while the bubble — acting like an internal, temporary bandage — floats to the back of the eye, helping the edges of the hole approach each other leading to closure.

"No one likes that," she said. It can take weeks to months for vision to improve depending on various factors like degree of cataract after a successful surgery. There is also some risk that the surgery simply won't work, the hole will reopen or the retina will detach. This is uncommon, affecting only a small percentage of cases. But if a surgeon does 100 procedures a year, Skondra points out, "that could mean some really unhappy and potentially visually disabled patients."

Eye drops over surgery

She got the idea for the new approach at an ophthalmology conference. A speaker, Ron Gentile, MD, FACS, a professor of ophthalmology at the New York Eye and Ear Infirmary, mentioned that he was trying something new. Instead of jumping straight to surgery, he sometimes gave patients two types of eye drops to dehydrate the retina and decrease the swelling around the hole. As the fluid left and swelling decreased, the edges of the macular holes would sometimes creep back together, closing the hole. He tried that on about ten patients and some of them recovered without needing surgery. "What an interesting idea," Skondra thought. "I want to try it."

Her first case was fairly convincing. The patient in Chicago had only one good eye, and that eye had a small macular hole with swelling around it. He was afraid to have surgery since it was his only good eye. So, Skondra explained the eye-drop approach, and the patient was on board. She gave him two standard drugs: prednisolone, a steroid, and ketorolac, an anti-inflammatory. Then she added a third drug, an idea she got from a former mentor, Demetrios Vavvas, MD, PhD, an associate professor of ophthalmology at Harvard. That drug, brinzolamide, helps pump fluid out of the eye to lower pressures for patients with glaucoma.

All three were off-label uses, but they were unlikely to cause damage and "if the hole doesn't close," she reasoned, "we can still operate."

After two weeks, patient No. 1's hole had nearly closed. Then, he went on vacation to Mexico and stopped using his eye drops. The hole promptly reopened. When he came back, Skondra put him back on the drops. Within a month, the hole was closed.

"OK," Skondra thought. "It worked, just as we hoped, and we avoided surgery. The fact it got better with drops, worse after he stopped and then better after we restarted them is supporting the hypothesis that decreasing the swelling promotes hole closure as Dr Gentile's "hydration" theory suggested."

"If you Google this, you will not find it."

She didn't try it again for almost a year since she did not have a patient that seemed to be a good candidate. But in January 2017, now at UChicago Medicine, a new patient, a hospital administrator, came into her clinic with a small but full-thickness macular hole. They discussed surgical options at length, then Skondra mentioned the drops.

"I've done one patient and it worked," she explained. The patient opted for drops and the hole closed. The third patient, who came to Skondra from another physician, had also a small macular hole. He responded to the drops at first, but his original doctor told him to stop taking them. The hole came back and required surgery.

The fourth patient, however, a UChicago Medicine nurse, was what Skondra would think of as a textbook case. Marianne Strickland, RN, had just bought new glasses in March. She made an eye appointment in early May because her eyes felt strained and her central vision seemed "a little blurry." She blamed her allergies.

The standard eye exam, however, revealed a small macular hole. Skondra explained the options: surgery, which is effective, or a less invasive but unproven option: eye drops. "If you go to any other eye specialists," she explained, "they will ask, 'What is your doctor thinking?' If you look it up on Google, you will not find any mention of this. But it may save you from an operation on your eye."

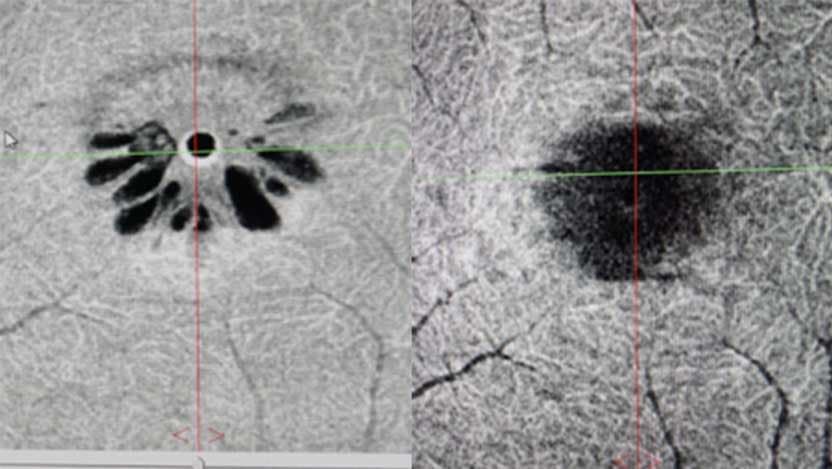

For Strickland, that was an easy choice. Her macular hole was small. There was some swelling around it as indicated by tiny cysts resembling the petals of a daisy. The hole had been there for at least three to four weeks probably longer, Skondra said. "Four days after we started the drops, the cysts were all gone and the hole was smaller.

Two weeks later, the hole had closed.

"I'm so glad I had this option," Strickland said after a checkup. She used the eye drops three or four times a day, about 10 minutes ibetween each set. As soon as I started using the drops, it started getting progressively better while it was the same or even getting worse for weeks before seeing Dr Skondra and starting the treatment."

Skondra tells patients to continue to use the drops for a while, even after their vision returns to normal. She slowly withdraws the eye drops, one drug at a time after the first month.

"I'm an eye surgeon," Skondra said. "I love complicated surgery. But it's so much more rewarding when I can fix a problem without cutting someone's eye open. That gives me satisfaction: to help them get their vision back, without significant risk. Patients prefer that."

.jpg%3Fsc_lang%3Den&w=3840&q=75)

Dimitra Skondra, MD

Dr. Dimitra Skondra is a highly respected, board-certified retina specialist, with a particular focus on the medical and surgical treatment of vitreoretinal diseases. She in an expert in delivering care for diabetic eye disease, retinal detachment, age-related macular degeneration, retinal vein occlusions, eye trauma, proliferative vitreoretinopathy and intraocular infections.

View Dr. Skondra's physician profile