Graphic medicine: Coming to a doctor's office near you

In a remarkably short time, comics have grown up, sloughing off their superhero chains to become a respected medium for adults.

Now, boasting an impressive versatility, they’re coming to hospitals, medical schools and doctors’ offices near you.

This confluence of comics and medicine — coined graphic medicine in 2007 by U.K. physician Ian Williams — has become a vibrant area of study. Just as the works of Art Spiegelman, Chris Ware and Alison Bechdel have proven that comics can tell important stories about complex family relationships and the Holocaust, graphic medicine has flexed its muscles to deftly handle such emotional and weighty issues as illness and dying, and effectively deliver complex information to professionals and patients alike — even as it provides an insightful, unsparing critique of the health care system.

For Brian Callender, MD, an interest in capturing the patient experience first drew him to graphic medicine, but it was the impressive array of possibilities that prompted him to take up serious study of the burgeoning field.

Callender, assistant professor of medicine, is the co-director of the Scholarship and Discovery Global Health Track at the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine and one of the core faculty at the University’s Stevanovich Institute on the Formation of Knowledge.

Comics is a great way to tell the story of what happens in medicine and depict the experience of illness.

Long interested in the health humanities and narrative medicine, Callender’s curiosity about using comics in his work prompted him to talk with Hillary Chute, the comics scholar then at UChicago, who told him about the field. Callender was hooked.

He eagerly explains the strengths inherent in comics.

“Comics is a great way to tell the story of what happens in medicine and depict the experience of illness,” he said. “I am particularly struck by how illness affects an individual’s sense of time and space.”

For example, he said, imagine what a set of stairs looks like to a healthy person — simple access to the rooms above — versus how it appears to a person with a serious lung condition — a barrier that effectively cuts the individual’s home in half. “Illness often forces one to live in the present with their current symptoms while questioning the past and future,” Callender said. “With comics, one can really play around with the flow and pace of a narrative, or even parallel narratives, across particular spaces and time periods.”

Picture, he said, how different time feels for a busy physician or nurse in a hospital versus the patient confined to a hospital bed. “I think comics is the best medium to get that story across,” he said. And as a clinician, he is also interested in

the practical use for comics in patient-care situations.

But Chute’s even more important contribution, possibly, was introducing Callender to Comic Nurse.

Pioneers in graphic medicine

In 1994, MK Czerwiec (pronounced Sir-wick) started her nursing career at Illinois Masonic Medical Center in Chicago’s Lakeview neighborhood. She was assigned to the HIV/AIDS care unit at the height of the epidemic when there was no cure and the emphasis was on care.

The community hospital’s physicians and nurses were powerless to stop their neighbors and friends from dying.

“It was a very difficult time,” Czerwiec said. “And I was trying to figure out how to keep doing this difficult work and yet still stay connected.” She said she tried journaling, but found that the words didn’t come. She tried painting, but that also “didn’t capture the whole story.”

When the AIDS unit closed in 2000, it clearly marked a huge victory against a horrible disease, but it also left Czerwiec saddened as longtime co-workers went their separate ways. She struggled to express this bittersweet mix of emotions. “One day I sat down, and I basically stumbled into making a comic,” she said. “I realized that the combination of image and text in sequential fashion really helped me organize my thoughts. It just worked.”

She received supportive feedback and kept cartooning. “I felt like I’d found a medium where I could really express myself,” she said. Comic Nurse was born. She went back to school to earn a master’s degree in medical humanities and bioethics from Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine, where she is now artist in residence and teaches seminars. She is also a senior fellow at the George Washington School of Nursing Center for Health Policy and Media Engagement.

Her 2017 graphic nonfiction book, Taking Turns: Stories from HIV/AIDS Care Unit 371, is not just a poignant memoir, but also a gripping oral history of the AIDS unit and that period in Chicago.

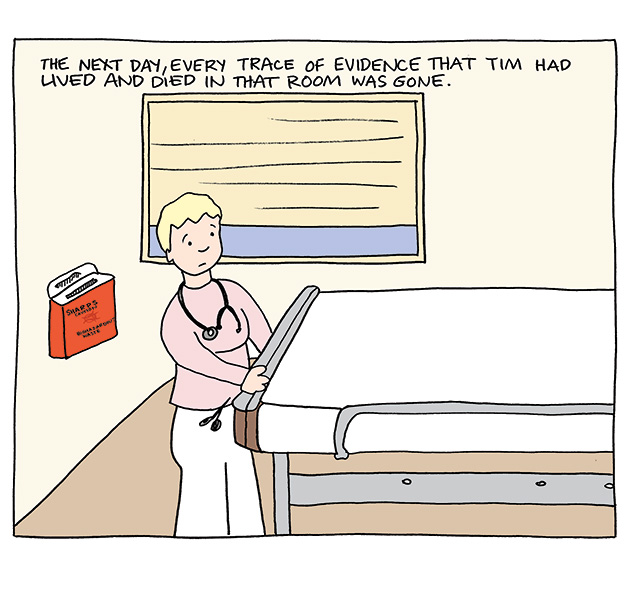

In this short excerpt from Taking Turns: Stories from HIV/AIDS Care Unit 371, MK Czerwiec depicts the passing of a patient on an HIV/AIDs unit at the height of the AIDS epidemic in the 1990s. A particular strength of comics is the ability to depict space and time, which are both important aspects of the illness experience. In these images, Czerwiec conveys, by varying the perspective, the bedside experience of a dying patient, his mother, and provider. The end panel, in depicting the now-sanitized room where a patient recently died, is an abrupt visual shift from the previous panels that mirrors the abrupt emotional shift expected of providers who will have to care for the next patient to occupy that bed—Brian Callender, MD (click to enlarge each image).

In this short excerpt from Taking Turns: Stories from HIV/AIDS Care Unit 371, MK Czerwiec depicts the passing of a patient on an HIV/AIDs unit at the height of the AIDS epidemic in the 1990s. A particular strength of comics is the ability to depict space and time, which are both important aspects of the illness experience. In these images, Czerwiec conveys, by varying the perspective, the bedside experience of a dying patient, his mother, and provider. The end panel, in depicting the now-sanitized room where a patient recently died, is an abrupt visual shift from the previous panels that mirrors the abrupt emotional shift expected of providers who will have to care for the next patient to occupy that bed—Brian Callender, MD (click to enlarge each image).

Czerwiec was a pioneer in graphic medicine, joining Ian Williams and other early adopters at the inaugural international graphic medicine conference in London in 2010. She brought the conference to Chicago in 2011, where she met Vineet Arora, MD, assistant dean for scholarship and discovery.

“MK has become a wonderful friend and colleague to so many of us,” Arora said. “In the areas where improving care meant empowering nurses or patients, that’s where we found her tools to be very helpful.”

Arora, who is now associate chief medical officer for clinical learning environment at the University of Chicago Medicine, focuses on using novel learning techniques to improve the quality of care.

“We’ve all heard of death by PowerPoint,” she said. “A physician recently said to me that a noon lecture would be a good time for their lunch and nap.” So, Arora is always on the lookout for effective ways to get someone’s attention and convey complex information.

In other words, the perfect job for graphic medicine.

Simple, versatile and effective

Arora first discovered Comic Nurse on Twitter and recruited Czerwiec to aid with a project to help a mentee who was working with her to improve handoffs. Some outpatient clinic patients fall through the cracks and miss the opportunity to meet their new primary care physician. As part of the 2012-14 study, Czerwiec created comics to include in a new, patient-centered transition packet. A 2015 paper in the Journal of General Internal Medicine reported the results: More than 45 percent more patients recalled receiving the packet — and the number correctly identifying their new doctor soared to 98 percent from 77 percent.

Arora was impressed. She asked Czerwiec to help with a National Institutes of Health-funded project empowering nurses to help hospital patients get a good night’s sleep.

The SIESTA Project — Sleep for Inpatients: Empowering Staff to Act — also saw impressive results.

“The patients in the SIESTA unit where these comics were displayed and the nurses received training were much more likely to report no disruptions from nighttime vital signs or from medication,” Arora said. “Nighttime room entries dropped by 44 percent in the SIESTA unit.”

A third project, still in progress with two of her colleagues, aims to empower patients to ask to see electronic health records during their clinic visits.

“One of the things that’s amazing about graphic medicine is that the simple medium is so versatile in the work it can do,” Czerwiec said. “I think that’s partly responsible for the success of the graphic medicine movement, because it resonates with so many people from so many different perspectives.”

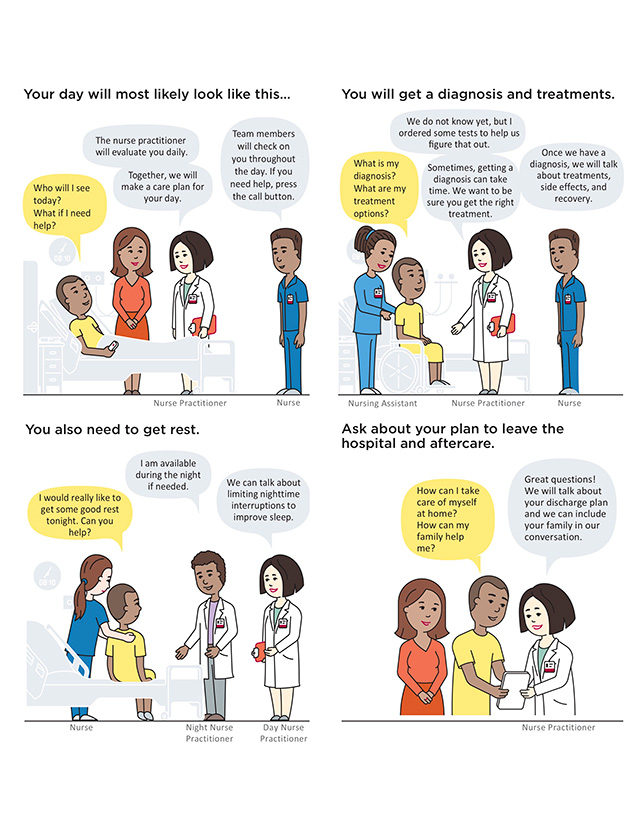

Callender, a hospitalist and medical director for the Advanced Practice Service’s short-stay unit at the University of Chicago Medicine, was concerned about patients’ understanding of the experience of being hospitalized. He worked on a patient education project in collaboration with the Illinois Institute of Technology’s Institute of Design — with grant support from UChicago’s Bucksbaum Institute for Clinical Excellence — to create a graphic-oriented guide that depicts the general hospital experience as a narrative. In follow-up surveys, more than 75 percent of patients who received the pamphlet agreed it was easy to read and understand, improved understanding of the hospitalization and care team, and was visually appealing. An additional collaboration between radiation oncologist Daniel Golden, MD, MHPE, the Institute of Design and the Bucksbaum Institute to educate patients about radiation therapy recently won an award of distinction from the Center for Plain Language.

This graphic-oriented guide for patients in the short-stay unit depicts the general hospital experience as a narrative. Callender worked on the project in collaboration with the Illinois Institute of Technology’s Institute of Design, with grant support from the Bucksbaum Institute for Clinical Excellence (click to enlarge).

This graphic-oriented guide for patients in the short-stay unit depicts the general hospital experience as a narrative. Callender worked on the project in collaboration with the Illinois Institute of Technology’s Institute of Design, with grant support from the Bucksbaum Institute for Clinical Excellence (click to enlarge).As part of the Comprehensive Care, Community and Culture Program’s Artful Living Program, Callender and social worker Kathryn West implemented a series of graphic medicine workshops in which patients create their own comics about their illness, life and community. They recently used a wellness graph exercise in one workshop that helped patients better understand how far they had progressed in their treatment, despite recent setbacks. On a large piece of paper, patients drew two axes, with time across the bottom on the x-axis and wellness on the y-axis.

“We initially struggled with how to define wellness,” Callender said. “Rather than give patients an arbitrary scale, we settled on letting them place their experiences and memories on a scale that they defined. By placing the experiences in relation to one another, the relative difference would indicate the magnitude of the experience.”

One patient had suffered significant injury from a 25-foot fall, with continuing health problems as a result. Callender said he thought the exercise not only helped this patient see how far he had progressed from the traumatic event, but also allowed him to envision a healthier future, which the patient had illustrated on his wellness chart as a sailboat on a lake.

Teaching graphic medicine

With the support of the Stevanovich Institute on the Formation of Knowledge, Callender and Czerwiec teamed up to develop and teach an undergraduate course, Graphic Medicine: Concepts and Practice, during Winter Quarter 2019 that introduced the students to the wealth of graphic memoirs written by patients and caregivers. As part of the course, students also were required to pick up pencil and ink — or crayons — themselves.

“It’s not usual that in the first class of a college course they give you a box of crayons,” said Tirtzah Harris, a second-year creative writing major.

That’s by design.

“One of the reasons I very intentionally use crayons is that there’s an access point there where people pick up from where they left off in fifth grade or third grade,” Czerwiec said. “That’s another wonderful thing about this medium. It is a pretty low bar to entry as long as you can make clear what you’re trying to communicate.”

Czerwiec said that people are programmed to easily read the facial expressions and emotional symbols used in comics.

“You can communicate a tremendous amount of information with a pair of eyebrows,” she said.

To engage the class, many of whom are premed students, and demonstrate the full power of graphic medicine, Callender and Czerwiec assigned a body-mapping project that forced the students to confront their own health issues, while incorporating their weekly comic journaling work.

On the first day of the project, the students enthusiastically helped each other tear off lengths of heavy-duty brown construction paper, tape them to the walls and trace outlines of their bodies. Most opted for the standard, anatomic figure with arms and legs out, but one woman drew her arms akimbo, and one man opted for something closer to the dead body pose.

Immediately, experience and creativity began fleshing out the outlines.

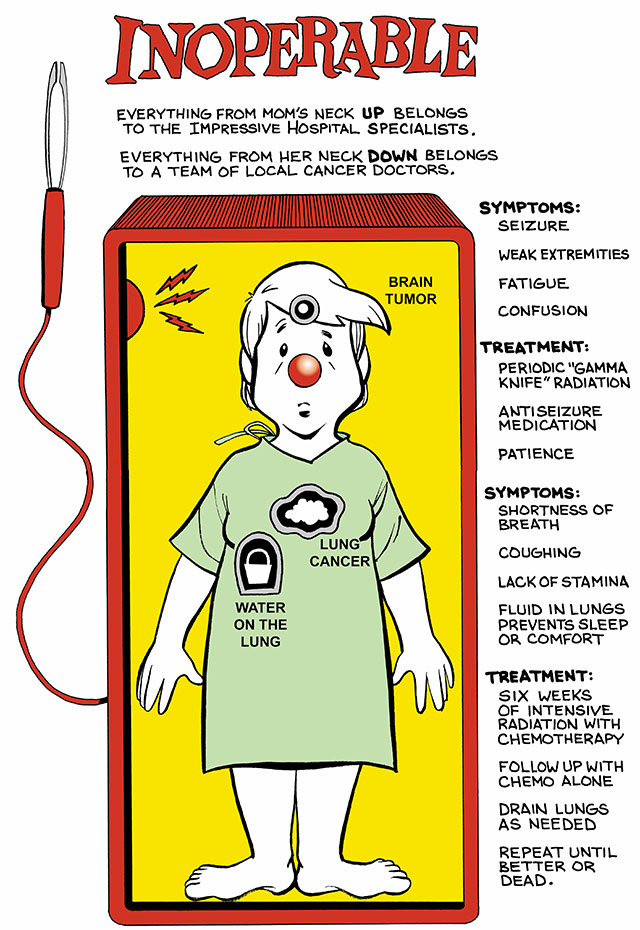

In this image from Mom’s Cancer, Brian Fies creates a compelling visual metaphor of disease as a game. Drawing upon the childhood game of Operation, the image can be read from the patient’s perspective as the feeling of being treated as if a diseased patient is merely a game for physicians to play. The combination of words and pictures inherent to comics allows for bodily depictions of cancer linked to text that describes symptoms and treatments, but also serves as a critique of specialization that fragments the body into different regions that “belong” to different teams of doctors at the expense of treating the patient as a whole person (click to enlarge).

In this image from Mom’s Cancer, Brian Fies creates a compelling visual metaphor of disease as a game. Drawing upon the childhood game of Operation, the image can be read from the patient’s perspective as the feeling of being treated as if a diseased patient is merely a game for physicians to play. The combination of words and pictures inherent to comics allows for bodily depictions of cancer linked to text that describes symptoms and treatments, but also serves as a critique of specialization that fragments the body into different regions that “belong” to different teams of doctors at the expense of treating the patient as a whole person (click to enlarge).Katie Akin’s body map sprouted a three- dimensional nose, anxiety lightning radiated from the head and positive feelings emanated from the heart. Akin, an English language and literature and political science major, later added scars and birthmarks she hadn’t thought about in a long time, and even her sister’s scar to her own arm.

“I was there when she got the injury, and I still feel kind of guilty about it,” she said.

More than one student commented how the body isn’t just a record of physical events but also of memories and emotions.

For Kelsey Hopkins, a biochemistry major applying to medical schools, the course was an opportunity to remind herself of why she wants to be a doctor.

“I didn’t know that graphic medicine was such a huge field before I started this class,” she said. “It is a unique way to share patients’ experiences.”

Jason Xiao, a biological sciences major, had his classmate outline his body as he lay on the floor, arms and legs splayed out: the iconic crime scene visual.

“The mapping reminded me of situations in which the body actually is outlined and examined in meticulous detail,” he said. “This evolved into the ‘dead body outline.’” He said that early choice continued to shape his perspective as the project progressed. For example, he drew memories, formed during his lifetime, leaving his body one by one.

Possibly the most widespread and most common examples of graphic medicine are the memoirs written by people diagnosed with diseases and their caregivers. It is in these works that Callender, Czerwiec and others say the medical community receives invaluable information about how diseases and treatments affect patients physically, emotionally and mentally, and insightful critiques of physicians, nurses and the hospital experience.

“Images have long been a part of medical practice and discourse,” Callender said. “The more recent addition of comics to medicine is a welcome contribution. These stories and images provide a broader depiction and critique that enriches the iconography and experience of medicine.”

The lessons were not lost on these future physicians.

“The class was cathartic, powerful both in the act of creating but also in relating to those who have gone through such life-changing experiences,” Xiao said.