Perfecting MRI as a breast cancer screening tool

Mammography is the most routinely used imaging tool to screen for breast cancer, but it is not the best option for the those with dense breasts. (Approximately 40% of breasts fall in this category.) Dense breast tissue obscures small masses, making them difficult to detect by mammography. Individuals with dense breasts are at higher risk of missed diagnosis and, therefore, need additional imaging tests to rule out suspicious areas.

Mammography also often does not find invasive cancers until they are fairly advanced. Although mammography finds many ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) — or early-stage tumors confined to the lining of the breast milk duct — it does not reliably discriminate between DCIS that is not clinically significant and DCIS that will progress to become invasive and life-threatening.

MRI & Breast Screening

The use of magnetic resonance imaging, better known as MRI, for breast cancer screening offers significant advantages for those with dense breasts and/or with moderate to high risk for breast cancer. MRI is much more sensitive than mammography, meaning it can pick up even very small abnormalities, regardless of breast density or fatty tissue in the breast.

Importantly, MRI can find invasive breast cancers in some patients, especially those with dense breasts, years before they would be found by mammography. The earlier a breast cancer is diagnosed, the better the survival outcome.

MRI also has strong negative predictive value, meaning that individuals who receive negative findings on MRI can be confident that they do not have clinically significant breast cancer.

Although MRI has many advantages, there are still several hurdles to overcome before its wide adoption for breast cancer screening. For instance, conventional MRIs are much too expensive for routine screening of millions of patients.

The University of Chicago Medicine Comprehensive Cancer Center has built an interdisciplinary group of researchers and clinicians who are developing innovative and translational solutions to these challenges.

The team includes radiologists, medical physicists, oncologists and an experienced, dedicated staff of technicians and clinical research coordinators. The group has made several major contributions to the use of MRI for breast cancer screening.

Improving Diagnostic Accuracy

Gregory Karczmar, PhD, professor of radiology and co-leader of the Comprehensive Cancer Center’s Advancing Imaging Program, and colleagues developed faster and more clinically useful ways to obtain MRI scans. MRI is traditionally performed by administering a chemical substance known as a contrast agent and acquiring image scans every 60 to 90 seconds for up to 40 minutes. Although this method provides very detailed images, it does not adequately show the rate at which the contrast agent is being taken up by suspicious lesions, which is useful information in identifying cancer.

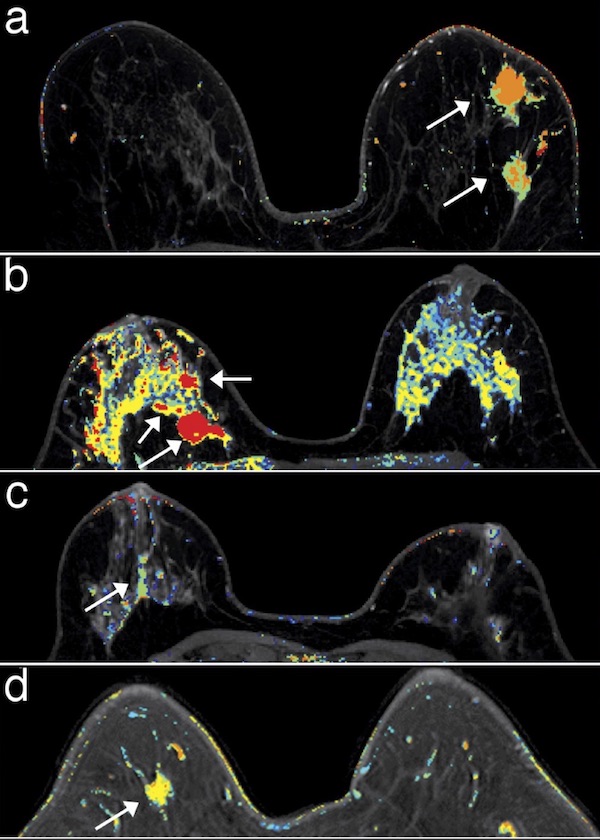

In order to obtain this information, Karczmar’s group developed a new technique called ultrafast dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE) MRI. The technique involves scanning the breasts on both sides every two to four seconds to accurately measure the activity of the contrast media, which can reveal the presence of cancer.

Karczmar’s lab was among the three labs that first demonstrated advantages of performing this type of MRI for breast cancer. They are also pioneering unique ways of analyzing this new type of data and have received a patent for novel quantitative parameters derived from ultrafast DCE-MRI that have potential to significantly increase diagnostic accuracy.

Reducing Time of Scan

The researchers also found a way to make ultrafast DCE-MRI even more effective by integrating it with abbreviated MRI. Abbreviated MRI is a five- to 10-minute scan that aims to reduce costs and increase convenience and efficiency compared to conventional scans by skipping unnecessary acquisitions.

Adding ultrafast DCE-MRI into abbreviated MRI screening can achieve effective results in 10 minutes or less. “Compared to conventional MRI, this has potential to substantially reduce costs,” said Karczmar.

Reducing Contrast Agents

Contrast materials are injected into a patient before imaging to help radiologists distinguish normal from abnormal areas. Although these materials are relatively safe, some patients may have adverse reactions.

To address these concerns, Karczmar and colleagues have developed techniques that require only 15%to 25% of a standard dose of contrast agent without loss of diagnostic accuracy. They have been able to show that lower doses of contrast agent have potential advantages for the detection of cancer, while reducing costs and concerns about adverse effects.

They also have developed an innovative MR method for detecting cancer without contrast media. This method, referred to as high spectral and spatial resolution imaging (HiSS) detects invasive breast cancer as reliably as conventional methods.

“Breast cancer screening without injection of contrast media would reduce costs, increase compliance with screening, and make it possible to perform MRI screening outside of hospitals, for example, in local malls and doctor’s offices,” Karczmar said.

A Greater Role for MRI

As a technology that can detect early breast cancer regardless of breast density, MRI is playing a greater role in breast cancer management, especially with new ways to make it faster, more convenient and less expensive. Many of the MRI methods newly developed by UChicago researchers are being used in routine clinical practice at UChicago Medicine. Additionally, Karczmar and his team are sharing these advancements with other institutions both locally and nationally through participation in a national multicenter clinical trial.

As a next step, Karczmar and colleagues are looking at new ways to use MRI to improve diagnosis of DCIS.

Bringing Breast Cancer Screening to the Community

African-American women are at highest risk of dying from breast cancers. Breast cancer screening is therefore crucial for women from underserved populations. Expense and convenience are critical factors for the underserved community on the South Side of Chicago. The University of Chicago team is partnering with local organizations such as the Metropolitan Chicago Breast Cancer Task Force to increase recruitment to clinical trials of new MRI screening methods.

“It’s important to improve community outreach so that members of the surrounding community can benefit from the new breast MRI methods being developed,” said Nita Lee, MD, Associate Professor of Medicine and Associate Director for Community Outreach and Engagement at the University of Chicago Medicine Comprehensive Cancer Center. “If we can catch more cancers earlier, fewer women will die from breast cancer.”

Breast Cancer Care

Our team represents expertise across the spectrum of breast cancer care: breast imaging, breast surgery, medical and radiation oncology, plastic and reconstructive surgery, lymphedema treatment, clinical genetics, pathology and nursing. Our comprehensive care approach optimizes chances of survival and quality of life.

Learn more about UChicago Medicine breast cancer care.