Sensory loss can be a warning sign of poor health outcomes, including death

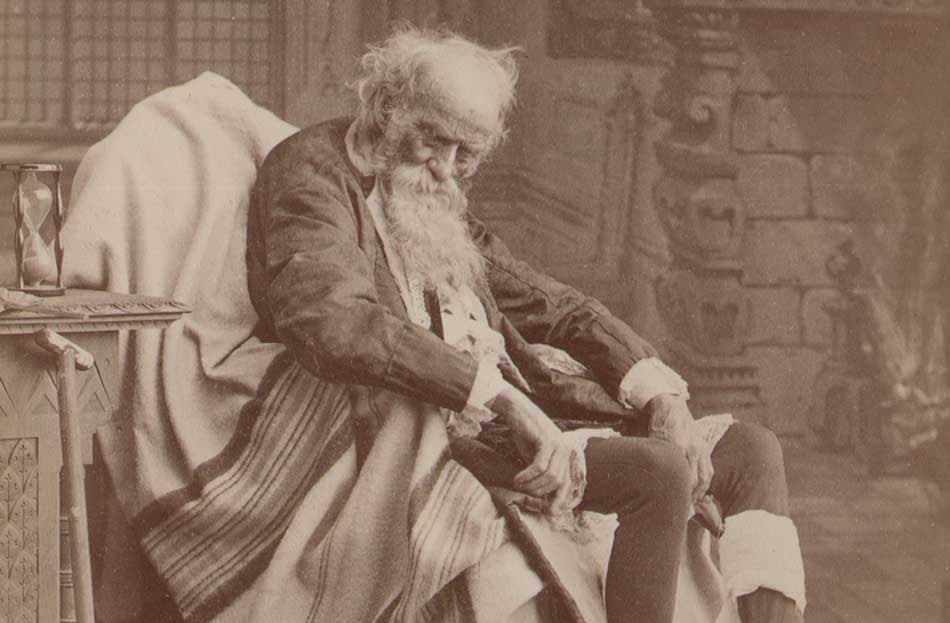

"Last scene of all that ends this strange, eventful history,

is second childishness and mere oblivion.

Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything."

- William Shakespeare, As You Like It

A long-term study spanning five years and including more than 3,000 nationally-representative older US adults has found that a natural decline of the five classical senses (vision, hearing, taste, smell and touch) can predict a number of poor health outcomes, including greater risk of death.

The study began with an assessment of how sensory dysfunction, or "global sensory impairment," a term coined by the researchers, affected physical and cognitive abilities in adults aged 57-85. The research team, led by Jayant Pinto, MD, professor of surgery at the University of Chicago, found that adults with worse global sensory impairment moved slower and had greater difficulty performing daily activities.

Five years later, the same people had more global sensory impairment. They moved even slower, were less active, and had more physical and cognitive disabilities. Compared to those with less sensory impairment, they even had a higher risk of dying.

"This is the first study to show that decreased sensory function of all five senses can be a significant predictor of major health outcomes," said Martha McClintock, PhD, the David Lee Shillinglaw Distinguished Service Professor of Psychology at the University of Chicago and a lead contributor to the study.

The paper, "Global Sensory Impairment Predicts Morbidity and Mortality in Older US Adults," published in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, follows a related 2014 study by the same group that focused on loss of smell as a predictor of death. The new study, however, found "no one specific sense that is primarily responsible for this phenomenon," said David Kern, PhD, coauthor of the paper and expert in sensation and perception research. "Olfaction (smell) is certainly a big predictor, but if you take smell out of the equation, the other four senses still stand as a significant predictor of health outcomes."

In the study, the researchers used validated tools and controlled for factors that could affect the results such as demographics, education level, drug and alcohol use, and weight. The researchers also teased apart any sensory loss that was due to environmental factors, such as exposure to loud noises that cause poor hearing. This allowed them to measure global sensory impairment as a function of aging alone.

After the five-year follow-up, the researchers found that greater global sensory impairment was associated with:

- Slower walking and less daytime activity;

- Greater difficulty performing instrumental activities of daily living;

- Lower cognition and worse self-reported physical health;

- Increased odds of death.

The research team is eager to analyze the next five-year data set of over 3,000 people, which will allow them to compare effects from five to 10 years of follow-up while trying to replicate the current findings. If the effects are even stronger at the 10-year mark, "we can be even more confident that global sensory impairment can predict long-term decline in the health of older adults," said Pinto.

Global sensory impairment can add insight into the mechanisms that drive health outcomes associated with aging. "There appears to be one or more specific physiological processes of aging so far unidentified that account for how the five senses decline together," Pinto said.

"The main mechanisms of aging could be inflammation, the lack of cellular regeneration, and/or other things," said McClintock. "But here we show that sensory function of all five senses is depending on some common mechanism, and this mechanism is predictive of getting sick."

The researchers point out that studies like this one could influence health policy and give physicians a valid tool to predict and treat a wide range of illnesses.

But there is a challenge: "People's sense of how good their senses are, is not very good," said McClintock.

"We are, however, moving to a point in society where you can test your senses on your own through various websites and apps," Pinto said. "Our group is working on an app right now to test smell. This could give people more control over their own health. Similar tests for general sensory function can move in that same direction," he added. "We can now predict how changes in our senses can influence activities we think are really important, like walking, moving, and living."

This study is part of the National Social Life, Health and Aging Project (NSHAP), a national probability sample of 3,005 home-dwelling older U.S. adults who were assessed at baseline (2005-2006), and then five years later (2010-2011).

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health including the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (Chronic Rhinosinusitis Integrative Studies Program), the Institute for Translational Medicine at the University of Chicago, the McHugh Otolaryngology Research Fund and the American Geriatrics Society.

Additional authors were Kristen E. Wroblewski, MS; Megan Huisingh-Scheetz, MD, MPH; Camil Correia, MD; Kevin J. Lopez, BS,; Rachel C. Chen, MD; L. Philip Schumm, MA; and William Dale, MD, PhD. All authors are affiliated with the University of Chicago. David W. Kern was affiliated with Northeastern Illinois University, in Chicago, at the time data were analyzed. Linda Waite is the principal investigator of NSHAP, a transdisciplinary effort with experts in sociology, geriatrics, psychology, epidemiology, statistics, survey methodology, medicine and surgery collaborating to advance knowledge about aging.