Fine-tuning multiple sclerosis drugs to make good treatments better

"When I was a resident, we had three people in the hospital at all times with multiple sclerosis complications," said Anthony Reder, MD. "Now, it's maybe one or two a month. There's been a huge change in how we are able to treat it and how active the disease is."

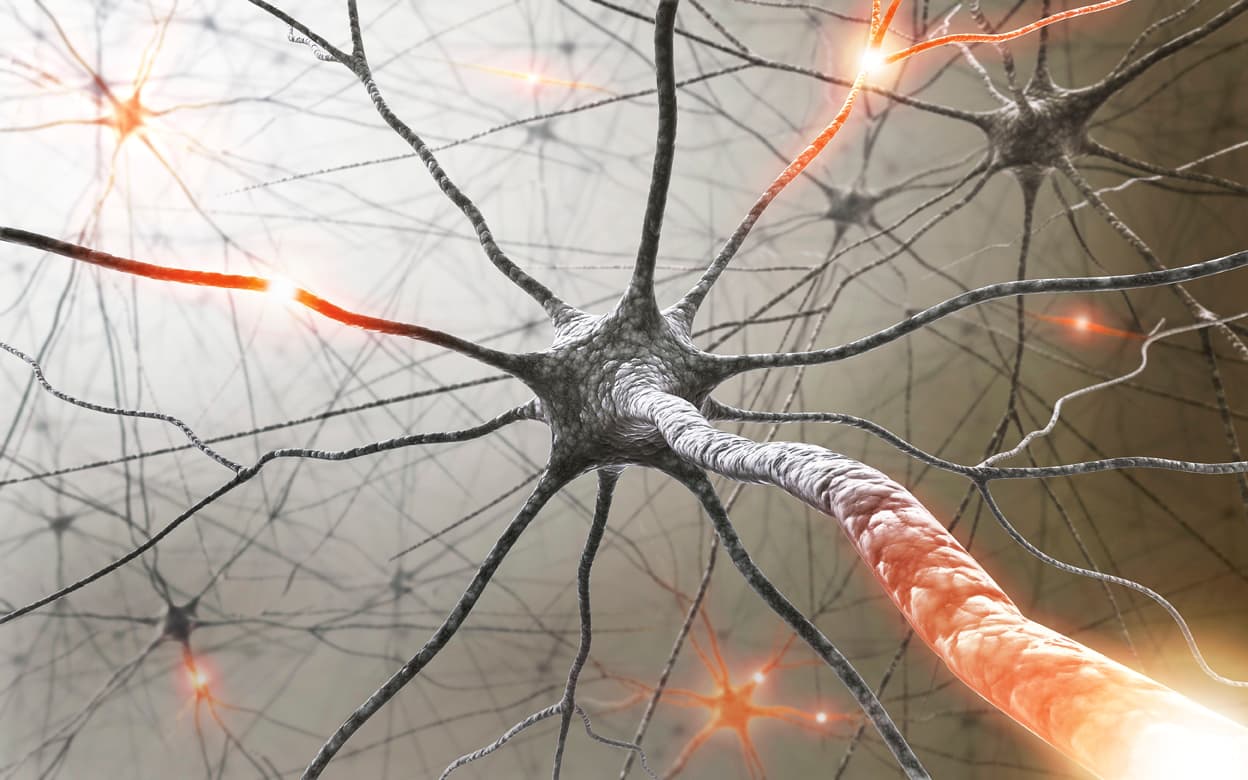

While there is no cure for multiple sclerosis (MS) — a chronic autoimmune disease of the central nervous system that can cause fatigue, difficulty with mobility and coordination, visual problems, and altered sensation — several advances in treatment have altered its course. Treatment with interferons, drugs based on proteins that control the defense mechanisms of the immune system, can limit attacks of MS symptoms, delay progression of the disease, and help repair damage to the brain and nerve tissue. Interferon-based drugs have been shown to work since their first clinical trials for MS in the 1980s — but exactly how they work isn't as clear.

Reder, who is a professor of Neurology at the University of Chicago Medicine, is working to understand the basic mechanisms of interferons and other drugs for MS. With the help of advanced genetic analysis and bioinformatics tools, he and his colleagues hope to improve these already promising treatments, and even apply them other neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's and Parkinson's.

Interferons, like many medical breakthroughs, were originally developed for other uses. They are an anti-viral drug, meant to boost the immune system's response to viruses and other pathogens; they have even been used to treat some cancers. Multiple sclerosis was originally thought to be a virus, so researchers tried it there as well-and they worked, not because MS was caused by a virus, but because the interferons reduced inflammation in the nervous system that ultimately caused symptoms.

"It's like aspirin," said Reder. "Nobody knew at Bayer at the turn of the century that a pain drug was going to be good for preventing heart attacks and strokes too. And we've now repurposed interferons."

Researchers now know that MS is an incredibly complex disease, possibly caused by a number of genetic and environmental factors. Inferferons reduce inflammation, but they also activate up to 5,000 different genes that can have varying interactions that lead to other downstream effects. For instance, MS patients taking interferons live up to 10 years longer than those who don't. This could be because interferons reduce inflammation and limit nervous system damage, or it may be a combination of other, unknown factors that increase longevity. Reder is working with scientists at the University of Chicago Center for Research Informatics to analyze the genetic responses of patients to new iterations of MS drugs. The data produced by this analysis allows them to spot patterns caused by one treatment or another, and identify potential targets for future improvements. Reder likened it to adjusting a proven recipe-while it may be good as is, testing the addition of different ingredients may make it even better.

Reder's work is partially supported by the Illinois Lottery's MS Project. Since 2008, sales from special scratch off tickets have supported their MS Research Fund. The Lottery, with the support of the National Multiple Sclerosis Society, distributes grants to neurologists, researchers, and clinicians treating MS in Illinois. So far the fund has raised more than $9 million for research, and now distributes $2 million in grants per year.

"It's been really good for us, and I think it's paid off for the state," Reder said. "It's very impressive, and I think the state of Illinois should be very proud of the MS Project."

Reder said he hopes this and other funding can continue to support more basic research on the mechanisms of MS and other neurological diseases. While advances in drug development have a direct effect on patients today, learning more about the basic building blocks of how and why they work could lead to bigger advances.

"It makes people look at a much broader perspective of how the drugs work," he said. "We've saved a lot of people from attacks and eventual progression, but there are still some patients who get the progressive forms of MS that keep getting worse. There's no treatment for that, and that's the latest direction of MS research. Any clues from our MS research might even help with treatment of many other neurological diseases."