Blending science and art: A UChicago graduate student explores the artistic side of her research

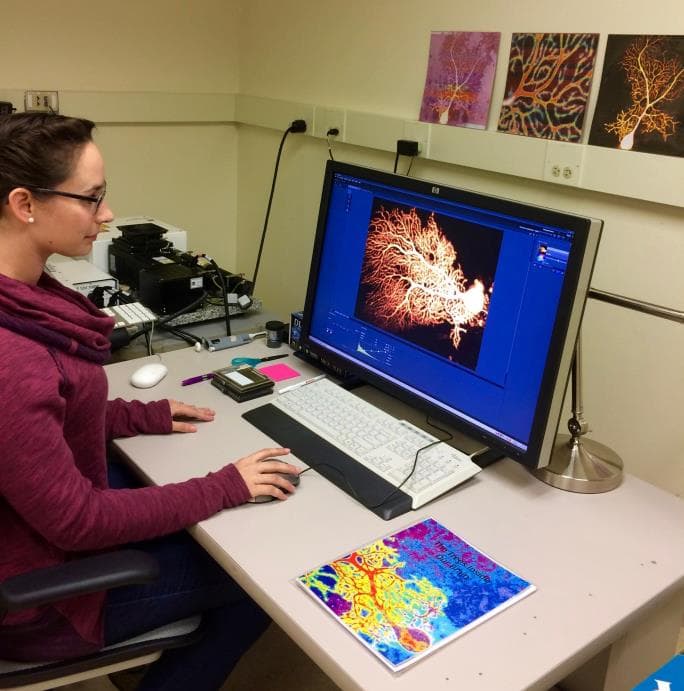

Graduate student Dana Simmons looks at an image she took of a brain cell.

"I grew up training as a ballet dancer and I always wondered how people can make such precise movements, especially while jumping or rotating in the air."

Dana Simmons, a graduate student in Neurobiology at the University of Chicago, became interested in neuroscience through her experiences with ballet.

"In ballet you have very complex movements. When you jump in the air you need to know where the ground is without looking at it," said Simmons. "I've always been interested in the cerebellum because it plays a big role in balance, posture, and learning new movements."

Simmons' research focuses on how autism affects the cerebellum, the part of the brain responsible for motor learning, posture, and balance.

"Generally, people think of autism as a social disorder, but a lot of patients also have motor symptoms," said Simmons. "It is an often overlooked symptom, and that's why we look at the cerebellum."

Simmons' work in the lab of Christian Hansel, PhD, professor of in the Department of Neurobiology, focuses on understanding how the patterns of communication differ for the brain cells (neurons) in an autistic versus non-autistic brain, using a genetic mouse model. Looking at neurons under the microscope, she measures the electrical currents to see if the learning and memory processes are altered. Simmons injects fluorescent dye into the cell and uses lasers to visually track the currents.

"Normally, when we take an image of a cell, we have the lasers on but not the background light. One day, I accidentally left the background light on and got all this extra color," said Simmons. "I thought – wow, this is art!"

Motivated by the artistic nature of her research, Simmons participated in the Bridge Residency program from the SciArt Center in New York, a program designed to have arts and sciences collaborate and create something that encompasses both. Partnered with Richelle Gribble, a California-based artist interested in art related to networks and interconnectivity, Simmons got to explore the artistic side of her science.

"I began looking at the images of the neurons more carefully and started looking for other patterns in nature that resemble this 'tree-like structure,' like river tributaries, blood vessel networks, antlers."

Simmons and Gribble created an illustrated book, called The Trees Inside Our Brain, to explain the science behind Simmons' research and included a scientific myth-busting section – Do we only use 10% of our brain? Is my brain full? Because of this work, Simmons will be presented with the New England BioLabs Passion in Science Award in the Arts and Creativity Category on November 3rd.

Simmons' science-art has found a home locally on the walls of the newly dedicated Grossman Institute for Neuroscience, Quantitative Biology, and Human Behavior and nationally as a page in Thermo Fisher Scientific's scientific coloring book, inspiring people with her work.

According to Simmons, exploring the artistic aspects of her research has enhanced her graduate school experience.

"I'm really interested in using science-art to improve science literacy. There can be a lot of resistance to science," said Simmons. "If I have really striking images, I hope that I can bring people in, encourage curiosity, and spark their interest."

To see and learn more about Simmons' art visit http://www.dana-simmons.com/