Smoking and its effect on telomeres, the shoelace caps of your DNA

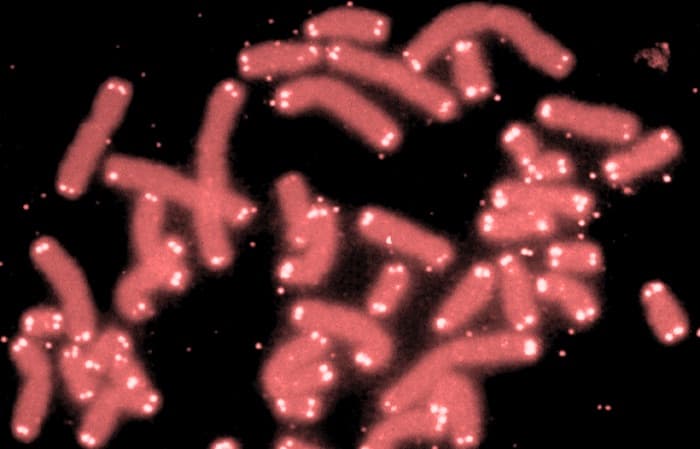

Your body accumulates wear and tear as you age, but it's not just muscle aches and bad knees. Your chromosomes get shorter too. When cells grow and divide, tiny bits of the ends of chromosomes called telomeres are lost. This is by design though-telomeres are there to protect the main parts of your chromosomes which contain genes. They're sections of non-coding DNA-bits that don't make proteins- attached to the ends of chromosomes that keep the rest of the DNA from breaking off when cells divide. They're like aglets, the plastic caps on the ends of shoelaces that keep the threads from fraying.

Scientists often view telomere length as a biomarker of aging. As you age, telomeres gradually shorten as cells divide and regenerate over and over again. But shorter telomeres, relative to where they "should" be given a person's age, have been implicated in a host of health problems, from cardiovascular disease to neurodegenerative disorders and some cancers.

The links with health present a chicken-or-egg problem though. Are telomeres shorter because of a person's health-related behaviors, lifestyle, and environmental exposures, or do shortened telomeres have something to do with the development of those diseases?

Brandon Pierce, PhD, assistant professor of public health sciences and human genetics at the University of Chicago, studies the role of telomere length as a biomarker of health, particularly as it's related to cancer risk-and that relation isn't always clear. For example, last year he and graduate student Chenan Zhang found that longer telomere lengths were associated with increased risk for lung cancer. This could be because the longer telomeres give cancer cells more chances to divide and proliferate, accumulating more and more cancerous mutations. But the same observation didn't hold true for other types of cancer, including breast, colorectal and ovarian subtypes.

The effects of smoking and exposures

Cancer is driven by a complicated mix of genetics, lifestyle, and environmental exposures. Pierce also studies how exposure to contaminants like arsenic contributes to genetic damage, including telomere shortening.

"Telomere length is potentially a marker of the biological effect of exposures" he said. "Harmful exposures can cause DNA damage across the entire genome, which includes breaks at telomeres and potential shortening of telomeres. And DNA damage is a key contributor to cancer."

One of the most obvious, cancer-causing exposures is smoking, although the research on its effect on telomere length is mixed. Some epidemiological studies show an association between smoking and shorter telomeres, others don't. In a new study published Nov. 17, 2016 in the American Journal of Epidemiology, Pierce and Zhang took another look at smoking's effect on telomeres in older adults by using a large set of longitudinal data collected over 16 years. Their analysis showed that smoking is indeed linked with shorter telomere length-and when taking into account differences between men and women, how long they smoked, and when they chose to quit, they may have found some reasons why previous studies have been inconsistent.

The new study used data from more than 5,600 participants in the Health and Retirement Study, a population-based study of American men and women over the age of 50. From 1992-2008, participants were asked about their current smoking status every two years, then in 2008 their telomere length was measured from saliva samples.

The study subjects were grouped according to smoking status during each two-year visit (never smoked, former smoker, or current smoker). Current smokers were also asked about how much they smoked per day. Previous studies that didn't show links between smoking and telomere length were all cross-sectional analyses-that is, they asked if a person was a current smoker, then compared their telomere length to someone who reported never smoking. It didn't necessarily account for someone who smoked a pack a day for 10 years, but quit a year before the study.

When smoking behavior over the 16 years of the new study was incorporated into the analysis, the researchers found a clear link between smoking and shortened telomeres in both men and women, although the association was much weaker for men when smoking status was measured near the time of telomere measurement. That's because short telomere length was also associated with poorer overall health in men and increased quitting, suggesting that men with shorter telomeres tend to quit smoking in later life because of poor health.

"Our findings not only strengthen the previously suspected connection between smoking and short telomeres, but also offer a fascinating explanation for why the association was hidden in older men," said Zhang.

A feedback loop on health

Again, Pierce says the impact of smoking creates another chicken-or-egg problem. We know smoking causes a variety of health problems, as well as telomere shortening. So, telomere length is an indicator of poor health, but poor health can also affect smoking behavior. There appears to be a feedback loop in place, but all the specific cause and effect relationships are not totally clear.

"We don't know whether telomere length is somehow a causal actor in that story of how smoking affects health. Smoking affects humans through a variety of mechanisms, and perhaps telomere shortening is one of them," he said. "So we're not claiming that telomere length is an important mediator of smoking's effects on health. But it appears to be an important biomarker of the damage smoking can do to the human genome.