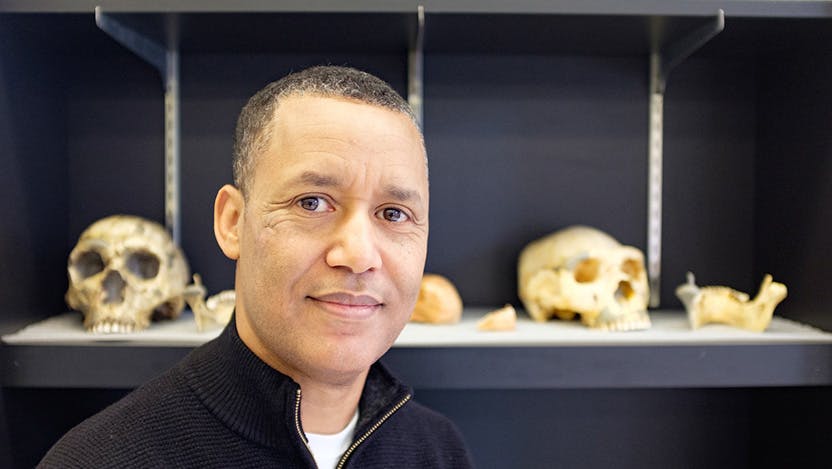

Paleoanthropologist Zeray Alemseged explores the origins of our shared humanity

In July 2015, Zeray Alemseged had the rare opportunity to meet President Barack Obama and the prime minister of his native country of Ethiopia, Hailemariam Dessalegne. Obama was making a historic visit as the first ever sitting US president to visit Ethiopia, and Alemseged, a paleoanthropologist, was tasked with showing him artifacts from the country's rich heritage of humanity.

Our species, Homo sapiens, was born in Ethiopia about 200,000 years ago, and our ancestors lived there long before that. Alemseged showed the two leaders some of the world's most famous fossils, including "Lucy," the 3.2 million year old Australopithecus skeleton discovered in Ethiopia in 1974 by Donald Johanson, and "Selam," a nearly complete, 3.3 million year old skeleton of an Austraolopithecus juvenile known as "the world's oldest child," discovered by Alemseged himself in the Dikika region of Ethiopia in 2000.

As Alemseged proudly showed off his country's heritage, he worked in a few digs at the then long-shot presidential candidate Donald Trump that impressed even Jon Stewart; but he left Obama with a message about humanity's shared history, dating back to when Lucy and Selam's descendants evolved in the Horn of Africa and spread across the globe. He wrote about the encounter later in Discourse, an East African humanities journal:

"We've come this far, a long odyssey since our species was born 200,000 years ago in Africa. All of us, particularly those in power and the aspiring ones, need to be reminded of a simple truth: the oneness of humanity."

It took six years of careful research and preparation before Alemseged revealed Selam to the world in a landmark publication in Nature in 2006. At the time, he was a senior scientist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, before settling in at the California Academy of Sciences two years later, where he worked for eight years as a senior curator and educator.

But in the fall of 2016, amidst stiff competition from other suitors, the University of Chicago convinced him to leave the California coast for the Midwest. The decision-joining U.S. News & World Report's top-ranked paleontology program in the country-was made easy by UChicago's storied history. The Walker Museum of Geology and Paleontology was established on campus in 1893, and some of the most famous names in the field, including Donald Johanson, Francis Clark Howell, and Sherwood Washburn trained or served on the faculty at UChicago. Continuing that history was appealing, Alemseged said, but so was the opportunity for collaboration offered at UChicago.

"The study of human evolution here has very deep roots," he said. "Continuing that legacy and thinking into the future is exciting, but when you leverage that with the ability to work with some of the brightest students in the world, the opportunity to collaborate with them is one of the great legacies a scientist could have."

Alemseged fills a niche in the Department of Organismal Biology and Anatomy as its resident paleoanthropologist, studying human origins and the environmental context of human evolution. The other senior researchers on the faculty occupy key branches on the evolutionary tree of life. Michael Coates studies the origins of early vertebrates and fish. Neil Shubin studies the first tetrapods and their transition to land. Paul Sereno covers dinosaurs and the emergence of flight, and Zhe-Xi Luo studies the origins of mammals.

Alemseged extends this expertise to the species that dominates our planet today, with a new breed of research that combines high-tech imaging analysis of fossils with traditional geology and field work. Using these tools, he explores the milestone events in human evolution since our split from the apes.

"With one foot in the field, he's a top-notch scientist who can use geology, biology and the latest technology in his work, and has a very good sense of public outreach," said Sereno. "I'm so happy he chose to come here, putting UChicago at the cutting edge of the newest research in human evolution."

Alemseged returns to Ethiopia every year for several months to continue work in the Afar, a paleoanthropological hotspot, collaborating with researchers from across the globe, including the National Museum of Ethiopia where the fossils are prepared and curated. "You can say that one-half of my lab is back there," he said. Despite the excitement of meeting world leaders and media coverage of major discoveries, Alemseged prefers the meticulous, painstaking labor of the field site and laboratory.

"I took six years to patiently work on Selam before even telling the world that I had this discovery. Six years, and then the moment came. We published our paper on the cover of Nature, and National Geographic came, the BBC sent a special envoy, CNN sent a special envoy. The moment of the announcement was fascinating, but then it passed and the following day was another stressful day," he said. "So what I enjoy the most is the quiet moments that I have in my lab in the process of making the little incremental discoveries, that when combined will allow me to tackle questions pertaining to those milestone events."

As he told Obama, the work of a paleoanthropologist helps us understand humanity's shared past, and ideally, emphasize less (or balance out) the cultural, linguistic, and political differences that drive so much conflict today. But equally important is understanding humanity's connection to nature. After all, we are just another animal, and our behavior has dire consequences for the entire planet.

"Today's humans, you and I, are so distinct, so far removed both anatomically and behaviorally from other animals. There is no other animal that has your brain. There is no other animal that uses computers and reflects on its origins," Alemseged said. "So, the key transitional moments in our evolutionary history that we paleoanthropologists establish will allow us to understand our links to our animal origins. Establishing those milestones allows us as scientists to know what the process was like, and allows the lay person to understand the links we have with nature."